"TV Station Fails to Overcome Deathrow Interview

Ban: Judge upheld Alabama prison official's prohibition against

media contacts with a female inmate, saying the policy was related

to security not content."

A judge last week denied a Montgomery, Ala.,

television station's request to interview a death-row inmate who

might become the first woman to die in Alabama's electric chair.

Montgomery County Circuit Judge Charles Price on April 24 declined

to remove a ban on media contact with such inmates.

WSFA/Channel 12 filed suit in Montgomery County

Court, asking Price to allow one of its reporters to speak to Lynda

Lyon Block, a woman scheduled to die on May 10 for the murder of a

police officer in 1993. The station claimed the First Amendment

forbids bans such as the one imposed by Prison Commissioner Mike

Haley. Station officials have not decided whether to appeal the

decision.

Block and her common-law husband, George Sibley,

were convicted on capital murder charges in the shooting death of

Roger Motley, a police office in Opelika, in a Wal-Mart parking lot.

Sibley also sits on death row but his execution date has not been

scheduled. Sibley and Block claimed self-defense in the shooting and

stated that police and courts do not have legal power over them.

In halting death-row interviews, Haley had issued

a memo saying he didn't wish "to publicize this heinous crime and in

so doing bring any recognition to Ms. Block." Montgomery County

Circuit Judge Charles Price heard arguments in the case on April 19

and agreed with prison officials that an interview with Block would

cause security problems. "There are a legion of cases that hold, as

this court does, that Commissioner Haley's decision to deny the

stated interview is not a denial of plaintiff's right of freedom of

speech," Price wrote in his decision. "This court finds that the

denial is based on security and control reasons and not content-related."

CCADP - George Sibley and Lynda

Lyon Homepage

George Everette Sibley, Jr. - born and raised in

South Bend, Indiana, and moved to Orlando Florida in 1976. He spent

most of his life designing and converting cars and engines into drag

racers, and also worked on street racers and circle track cars. He

owned his own car repair shop in Orlando, but closed it when he

couldn't find proficient mechanics to repair cars to his standards.

He enjoys reading, sport shooting, auto cross competing, and

political activism on libertarian issues. In recent years he became

a well-respected legal researcher and drafter of constitutionally

correct revocation and sovereignty-status documents.

Lynda Cheryle Lyon - born and raised in Orlando,

Florida, but has traveled throughout America. She is a professional

writer of columns, op-ed pieces and short stories for several

publications. She is a sailor, scuba diver, cross-country

motorcyclist, sport shooter, fisherman and billiards champion. She

has been active in community affairs as President of Friends of the

Library, as investigator for the Humane Society, President of the

Young Womens organization in her church, and State Vice-Chair of the

Libertarian Party of Florida, where she and George met. George

became Lynda's partner in her publishing business and wrote a column

about gun ownership rights in her magazine "Liberatus." They married

in 1992 and are raising Lynda's 11 year-old son, Gordon.

BOUND TOGETHER IN LOVE - AND DEATH

This is the incredible story of George Sibley and

Lynda Lyon - the only husband and wife in America sentenced to die

by electrocution - to be murdered by the State of Alabama for a

crime they did not commit They shot and killed a bad cop - Alabama

said it was murder but George and Lynda said it was self defense.

The dead officer was the only other witness as to how and why the

shooting began. His personnel file, that showed a long history of

abuse to the public, was hidden from the jury. The verdict was

predictable - guilty of capital murder The sentence - death in the

electric chair.

Written by Lynda Lyon in her own words, this

poignant narrative tells how despite torture, unsanitary conditions,

and almost dying for lack of medical treatment - George and Lynda

have never lost their love and loyalty to each other, and have vowed

they will always be soulmates - even to the day they are strapped

into the electric chair to their deaths.

"From Heaven to Hell," written by Lynda Lyon.

It was fate - and a libertarian philosophy - that

brought George and me together at a libertarian Party meeting in

Orlando, Florida, 1991. George had been attending for a year when I

entered the meetings for the first time. I was immediately at home

with the small but active group of intellectual activists, and

George and I were among a smaller group that together attended

political rallies.

A year later, my marital problems came to a head

and my husband agreed to leave the house to me and our son and to

start divorce proceedings. At that time, needing to enlarge my

fledgling publishing business, I accepted an investment partnership

offer from George, who had seen my potential as a writer and

publisher, and who had also seen an entrepreneurship opportunity for

himself.

Our partnership, which had began as friendship,

soon blossomed into romance - a true libertarian relationship of two

highly intellectual, fiercely independent individualists who live

passionately. We soon realized that we were soulmates - totally

compatible in every way. We married in 1992 and our love and

friendship has grown continually.

George helped me launch a new magazine -

"Liberatus" -and we published hard-hitting articles about political

corruption. We pioneered a revocation process that eliminated

driver's licenses, school board surveillance on my home schooled

son, IRS demands, and state revenue notices. Every document we filed

was challenged by the various agencies, but after we sent them legal

proof of our right to revocate, they went away. We taught others

this process in papers, video, and seminars. We spoke on local talk

radio. The local, state and federal agencies began to notice the

influx of revocation documents from Florida.

Our hell began, not with the agencies, but with

Karl, my ex-husband, who had decided to sue me for possession of the

valuable house. He petitioned the judge to allow him back into my

house until the case was settled, a preposterous idea. George urged

me not to go to Karl's apartment to try to reason with him, knowing

Karl to be a violent- tempered man. But I was desperate to keep my

home and was prepared to offer him a deal, so George went with me.

Karl let us in to talk, but he became angry at my attempt to

bargain. In a rage, he lunged at me. George managed to pull him off,

but Karl had sustained a cut from a small knife I had pulled out and

held up as a warning just as he had grabbed me. The cut was not

large or deep, and when we offered to take him to a medical center,

he refused, though he did allow us to bandage the cut.

George and I were arrested in our home at 2:30 am

that same night. Karl had called the police and told them we had

broken in and attacked him. George and I had never been arrested

before, never been in any trouble other than traffic tickets. We

were in shock - George's face was pale and grim, and I felt faint

when the deputy began to read us our "rights". They put us both,

hand cuffed, in the back seat of a patrol car and we tried to

console each other. We agreed not to make any statements until we

got a lawyer. I told him tearfully how sorry I was that he got

pulled into this mess between Karl and me, and he assured me that it

was all right, that he didn't blame me. I would have gladly borne

the ordeal myself to spare him this. At the jail, as George was

taken away, he looked back at me one last time and said "I love you,

Lynda". Those words sustained me through the next five days of hell.

Because we were charged with "domestic violence",

George and I could not make bond without a hearing, and we had to

wait five days for that. I was placed in a cell with 30 other crying,

arguing, loud talking women. I chose a top bunk on the far end, and

sat and cried. I was terrified, because I had recently been

interviewed on the radio about money being skimmed from the jail

accounts, and the sheriff had ordered the radio station padlocked

that night.

I could not eat those five days. The meat stank,

and the vegetables and whipped potatoes were watery. I lived on

whatever cartons of milk I could trade for my trays. I was astounded

that the long timers would eagerly bid for my tray, and I managed to

get paper and pencil as well. Writing helped me keep sane. I was

able to converse with some of the women who recognized me as "fresh

meat" and protected me from the lesbians and bullies. I called my

mother to see how my son was doing, and she told me that Karl said

he would make sure I went to prison and that he didn't want his son.

When I began crying, the others stopped talking and looked at me. A

large, black woman came over and hugged me to her ample bosom, and I

felt a strange kinship to these thrown-away, forgotten wives,

daughters, mothers.

The most humiliating experience was the strip

search. When ordered to strip for a body search, I froze. I had

never undressed for anyone except my husband and doctor. Silent

tears ran down my face as I disrobed, then turned to squat so they

could see if I had any drugs protruding from my rectum. When I

dressed, my face was red with shame. I felt violated, mentally raped.

I never did get over that.

George and I did get out on bond the 5th day. We

were sure that our ordeal was over and that we would soon prove our

innocence at trial. We were so naive.

It soon became evident that politics had entered

our case. Too late, we realized that our attorney had sold us out

for a job with the county. When our trial date arrived, our attorney

had done nothing - the witnesses had not been subpoenaed, nor

records we needed. George and I immediately fired him and asked the

judge for a continuance to prepare for trial. He said no - we either

plead "Nolo contendre" or go to trial that day; and if we were

convicted, we would be sent directly to prison for a mandatory

3-year term. Our attorney had an evil, satisfied look on his face

and I knew we had been set up. We were forced to sign "No contest."

We were still determined to fight it; we had a

month before sentencing. We filed papers exposing the corruption of

the judge and the denial of our right to a fair trial, sending

copies to the Governor, Lt. Governor, Chief Judge of Florida,

Attorney General, and the Sheriff. Friends and supporters flooded

these officials with faxes calling for an investigation, throwing

their offices in an uproar according to a secretary in the Chief

Judge's office.

We didn't show up for sentencing; we'd been

tipped off that Judge Hauser was going to send us to prison anyway,

under "orders." We had three days to file a temporary restraining

order in federal court, but the man who had promised to draft the

document never did, and a capias was issued for our arrest.

A friend in the Sheriffs department, and a member

of my church, called me the evening of the third day, his voice

shaking. "Lynda, the warrants for you and George came up on computer.

I just heard there's a plan to raid your house. They know you have

guns - they're going to use a SWAT team." I was incredulous. "A SWAT

team!" His voice became softer, sadder. "You and George have made a

lot of important people angry. They're going to kill you and then

say you shot at them first. " He paused, to let this sink in, then

said, "I've put myself at great risk telling you this. Please, get

out of Florida. They mean business."

George had heard this on the speaker phone. His

face was as somber as mine. As a last, desperate attempt to stop

this insanity, I called to talk to Sheriff Beary. I had interviewed

him when he ran for election. But he wouldn't come to the phone.

George and I were not criminals and we did not

want to become fugitives. But my friend had made it clear we had no

choice. At the invitation of a friend in Georgia to stay with him,

we loaded our car and George, my son Gordon, and I left Florida that

night.

The Shooting

We stayed in Georgia for three weeks, but we knew

we couldn't stay longer and endanger our friends. We decided to go

to Mobile, Alabama, a large port where strangers come and go

everyday, and figure out how to straighten out the Florida mess. We

stayed in a motel in Opelika, Alabama while waiting for our friend

to turn our remaining silver coin into cash, then we started out

October 4, 1993, for Mobile. On the way I spotted a drugstore with a

pay phone in front and suggested to George that we stop there so I

could get a vitamin supplement and call a friend in Orlando. After

Gordon and I came out of the store, he got back in the car to wait

while George and I made the call.

While I was on the phone, George stood by,

watching the traffic and people going by. He noticed one particular

woman in a red Blazer pull in beside our car. She got out and looked

at our car, a Mustang hatchback, with pillows stacked on top of all

our belongings. It later came out at trial that she had presumed

that we were transients, living out of our car, with a child

obviously not in school. Actually, I always carried my own pillows

when sleeping in motels. This woman's prejudicial presumption cost a

police officer his life, my son his mother, and George and me our

freedom.

Because I had run out of change for the phone, my

call was cut off, so we left. But as we were leaving the shopping

center I remembered my friend had an 800 number and I then spotted a

phone in front of Wal-Mart. So George pulled the car into a parking

space and he and Gordon stayed in the car while I walked to the

store to call. Unknown to us, the woman saw a police officer coming

out of a nearby store. She approached him and told him that we were

living out of our car and she was concerned about the child. She

gave him a description of our car and left.

Roger Motley was the supply officer for the

Opelika Police Department and hadn't been on patrol for years. He

was irritated that he had to stop and check on this situation. He

drove his car up and down the aisles, and when he found our car, he

stopped behind it.

I had my back turned while talking on the phone

and didn't see the officer pull up. When George saw the officer in

the rear view mirror, he got out of the car, closed the door, and

waited to see what the officer wanted. The officer approached George

with the typical "I'm the guy with the badge and the gun" attitude.

In a curt voice he demanded to see George's driver' s license.

George told him he didn't have one, and was prepared to get our

legal exemption papers from the car. The officer then decided to

arrest George and told him to put his hands on the car. George

hesitated, knowing this was arrest, yet he had done nothing illegal.

Motley, thoroughly irritated now, reached for his gun. When George

saw him go for his gun, he reacted instinctively and drew his own

gun. When Motley saw George's gun, he said "Oh shit'." and, with his

hand still on his gun, turned and ran for cover behind the police

car.

When I heard the popping noises, it took me a

couple of seconds to realize it was gunfire. I heard people yelling

and running to get out of the way. Quickly I turned and saw Motley

crouched beside his car, shooting at George. Fear gripped my

stomach. I cried, "Oh God, no!" and dropping the phone, began

running, ignoring the people scrambling for cover. I saw George

standing between the rear of our car and the right side of the

police car; he was holding his gun in his right hand, but his left

arm was hanging strangely. Motley didn't see me approach, and just

as I came to a stop I pulled my own gun and shot several times. He

turned to me in surprise, and as he did, one of my bullets struck

him in the chest and he fell backwards, almost losing his balance in

his crouched position. His gun was pointed at me and I prayed he

wouldn't shoot. Instead, he crawled into the car, and after grabbing

the radio microphone, he drove off.

I immediately ran to our car and got in. The

parking lot was quiet - everyone had sought shelter inside the

stores. I was shaken, yet incredibly calm. "What happened?" I asked.

George's face was extremely pale. "He tried to arrest me for not

having a driver's license." He shook his head in disbelief. "I was

going to show him our papers, but he didn't give me a chance - and

he went for his gun. " He looked at me, his eyes begging me to

believe him. "I couldn't just stand there and let him shoot me."

I did believe him. George is the most honest

person I know. He would not have placed himself or us in danger. He

took the law seriously. He was never the showoff gunslinger-type and

would walk away before being drawn into a fight.

I told him that I believed him, but that we had

just shot a cop and the whole police force would be gunning for us.

We had to get out of there fast. It was then I noticed his arm and

he raised it up to show me. With characteristic understatement, he

said simply "I've been hit." His arm had been pierced by a bullet.

Though blood was dribbling down his arm, it didn't obscure the hole.

I examined his arm and could see that the bullet passed through his

forearm and miraculously had not broken any bone or cut through a

tendon or artery. I had an advanced medical kit in the car and I

knew I could treat it later.

George maneuvered our car deftly through the

streets, trying to get us out of the area quickly while not

attracting attention. I tried to calm Gordon, who was crying and

shaking, and I looked at the map for the best route out. But we were

unfamiliar with the area and kept running into heavy traffic. Then

we picked up an unmarked police car and knew they were closing in on

us. We were going over 100 mph when we suddenly came to a crossroad.

We could only turn right or left. "Which way?" he asked. I was

clueless - I had lost track of where we were. He took a guess and

turned left.

We had gone only 1/4 mile down the country road

when we came up on a rise - and then we saw the roadblock, at least

20 cars. George slowed down, then pulled the car over to the side of

the road and cut the engine. He sat in calm resignation, then looked

over at me. I said quietly, "I guess this is it, isn't it?" He

nodded, then we both looked out at the policemen, detectives,

deputies -coming at us from all directions, guns drawn, shouting

"Get out of the car and put your hands up!"

It was an incredible, surrealistic scene, as

though I was experiencing a virtual reality game where I could feel

the action and motion, but then the game would end and I would go

back to living my real life again. My son's sobs brought me abruptly

back to reality. I rolled down my window and put out my raised hand.

"Stop!" I shouted. "I have a child in the car!" I could plainly see

the closest officer's face turn pale,and he quickly spoke into the

radio on his shoulder. "There's a child in the car!" he shouted. The

Opelika police never told these Auburn police this. The word was

quickly passed and then he said "Okay, ma'am, we won't shoot. You

can let the child go."

I talked to Gordon, calmed him down, then I

opened the door and let him out, told him to be a good boy and that

they would take care of him, and pointed him toward a plain-clothes

policeman. I gave him a last kiss, holding his handsome nine year-old

face in my hand, to get a last picture in my mind of the child I may

never see again. I watched him walk quickly away to the beckoning

officer and I felt as though my heart would break. I had planned his

conception, had nurtured him through sickness, homeschooled him. No

one could have possibly loved a child as much as I loved mine, and

he was walking out of my life only half-grown, unfinished.

As soon as Gordon was taken away, the police then

shouted at us to surrender. I turned to George and asked "What do

you want to do?" He had lost a lot of blood and was pale and tired.

"I don't know." I made a decision for us. I told the officer, "We

are not surrendering. You will have to kill us first."

For four hours George and I sat in the car and

talked. I held my gun where the officers could see that we were not

going to surrender peacefully. The officer continued to talk to me

to get information about us. George and I spent the time talking

about the shooting, as he explained to me what happened. We

discussed our plans for our future together, all gone. We discussed

the probability that if the officer died, we'd be charged with

capital murder and executed. If we decided to fight in court, it

could take years. We knew we did not want to spend the rest of our

lives in prison for an act of self-defense. We knew that it would be

our word against a cops' word, and we had already seen how corrupt

the justice system is. We then talked about suicide.

My religious belief is that suicide is wrong, but

now I was faced with the total hopelessness of our situation. I told

George that the only regret I had in all this is that I would not be

able to raise my son. We discussed all our options.

As dusk settled in, we saw the SWAT team position

themselves around us. The regular police had pulled back an hour

earlier. A negotiator got on the police car hailer and tried to talk

us into surrendering. We said no, that if they tried to come after

us we would shoot ourselves. He then tried to bargain with us. What

did we want? I printed my answers on notebook paper with a marker

and George held it out his window for them to read - to talk to my

son, to talk to the press, and to talk to clergy of my religion. He

agreed to all these things (he lied - they did none of them), but we

had to surrender first.

Finally, the showdown came. The SWAT teams had us

surrounded. We were told that if we did not surrender in 5 minutes,

they would lob tear gas through the windows of the car and take us

anyway. George and I had been sitting with our guns in hand. We had

planned to shoot ourselves in the head at the same time. George

looked at me with such sorrow and asked, "Would you mind if I stayed

in the car and shot myself while you surrender? At least you could

have some decision in Gordon's future."

I looked up at him with surprise, my eyes filling

with tears at the thought that this honest, loving, gentle man who

had waited over 40 years to find the right woman and found me,

spending all those years in patient waiting, should now die alone

with a bullet to his head. 'No," I said firmly, "I'm not going

anywhere without you. Either we surrender together or we die

together. I'll follow you, George - Whatever you want, I'm leaving

it up to you." A totally surprised expression came to his direct,

penetrating gaze. Until that very moment, he had not realized the

depth of my love for him, that I would rather stay with him, even in

death, and that I would trustingly place my life in his hands. "If

we surrender, it will be years before this is resolved." "I know," I

said, "but at least we'd be fighting this together."

He then took my left hand in his right, stained

with blood where he had tried to staunch the wound, and raised my

hand to his lips. "No," he said with renewed determination. "We will

surrender so we can fight this. We have to do whatever we can to see

that Gordon is taken care of, and to prove our innocence - if only

for his sake." For the first time in months, hope was in his voice "We

will fight this to the end, and it they still execute us, we'll die

knowing we fought for what was right." He then gave a tired smile. "Yes,"

I said with respect and admiration for my husband.

With a look of tenderness I'll always remember,

he leaned forward and kissed me, a gentle, parting kiss, perhaps the

last we would ever share. Then, at a nod from him, we laid down our

guns and exited the car with our hands up.

The Trials

George and I were placed in solitary confinement

in the Lee County jail in Opelika. The jail is small - the men's

section holds 100 men, the women's section - 25. I was taken to a 4-cell

unit in which I was the sole occupant. I was exhausted and numb - I

had been fingerprinted, photographed, strip-searched and questioned.

I had not eaten since breakfast and it was after 9:00 pm.

The cell block I was in was at the far end of the

jail and hadn't been used for almost a year. After the last

occupants had left, it had not been cleaned. One of the female

officers pointed out a cell and told me to put my things there, then

they left.

But five minutes later they came back and took everything

except the mattress, soap, toothpaste, and toilet paper. I stood

there, dumbfounded. "Why are you doing this?" I asked. "Orders," was

the curt reply and they locked me in the tiny cell.

George was treated similarly, locked in a cell by

himself, but under the watchful eye of a surveillance camera. The

bright fluorescent lights in our cells were not turned off for 10

days, and it was almost impossible to sleep.

The constant

temperature in the jail was 68 -degrees, and without, any covering,

not even a sheet, I developed hypothermia, at times awakened by

uncontrollable shivering. I would pace the cell to keep warm but I

was too exhausted to pace for long. George had no shoes or socks -

they had taken those from him- and he too, was suffering from the

cold.

By the 6th day of constant cold I awoke to intense shivering,

I was cold - inside as well as out; I was numb and could hardly move.

With great difficulty I crawled to the bars of the cell and tried to

raise myself, but couldn't.

About 30 minutes later they found me on

the cold cement floor, one hand grasping the bars, and they decided

to give me a blanket. I wrapped myself in it and slept for 18 hours

before my body temperature became normal.

I had to use my only pair of panties to wash

myself and hung them to dry overnight to wear each day. They

wouldn't let us shower, nor would they give us clean clothes. We

asked repeatedly to use the phone to call our families so they could

get lawyers for us, but they denied us that, too.

The constant cold

and bright light, the isolation, the starchy food - they all began

to take its toll - as planned. We were both taken before Judge

Harper for the initial appearance in handcuffs attached to

belly-chains, and shackles on our bare ankles.

One cannot imagine the pain of trying to walk

with shackles on your ankles, on bare skin. The proper procedure is

to place them on the pants legs, but the jailers deliberately put

them on our skin to inflict pain. George and I bore the pain without

comment - we were not going to let them gain satisfaction from their

torture. I still have scars on my ankles where the shackles dug deep

into my skin.

At both court appearances the media was there in

swarms. At the first appearance, Judge Harper - the star -

imperiously went through the routine of asking if we understood the

charge - capital murder - and that the penalty was death or life

without parole. Did we have lawyers or did we want the state to

provide them? We both looked at him in disbelief.

They all knew we

had been denied even one phone call - how could we have retained

lawyers? If George and I were not so exhausted and disheartened, we

would have insisted on handling our own case. But they would not let

us talk and discuss this.

The prosecutor had quickly figured out

from looking through my files and our legal papers that were in the

car that we were well-educated, and politically and legally astute.

He did not want us to handle our own case, thus the psychological

torture to force us to take their lawyers.

After we were appointed lawyers, suddenly

everything changed. They let us shower and use the phone. We

received all our bedding and basic toiletries. We began to receive

mail. Because George and I were so well known, the news of the

shooting went all around the country, and calls and faxes to the

Sheriff had come in asking about us.

My mother had called and begged

the Sheriff to let her talk to me but he curtly told her I was going

to die for killing a cop and hung up on her. A friend had traveled

all the way from Orlando to see what he could do for us and they

refused him. Letters began pouring in, but we didn't get them. The

prosecutor, judge and the Sheriff conspired to cut us off from all

contact with support.

Despite the cruelties I suffered, none was worse

than what they did to George. After they let us receive mail, a

friend sent us stationary, pens and stamps. It was a long shot but l

asked if George and I could exchange letters. Surprisingly, they

said yes. (We found out later that the prosecutor had the jailers

copy our letters for information.)

When George wrote, he told me

that the wound in his arm had been treated only once - at the

hospital right after we surrendered. Over a week had gone by and

they had not given him any antibiotics. Once, just before he was to

appear in court, an officer put peroxide in his wound and changed

his bandage. George wrote me that he could feel itching and could

smell infection setting in.

As angry as I was of their treatment of me, I was

more angry at their deliberate indifference to his obvious medical

condition. We had just been given permission to use the phone and I

called a friend and told him what they were doing to George.

He immediately put out an urgent fax message to our supporters

nationwide and we were told that the next day the Sheriff's office

was swamped with faxes and phone calls demanding that George be

properly treated immediately. Pat Sutton, a retired deputy, quoted

law and Supreme Court decisions to the Sheriff about the proper

treatment of prisoners.

Early the next morning George was taken to a

doctor who treated his wound and prescribed antibiotics. An officer

later told George they had been given a prescription for antibiotics

at the hospital, but the Sheriff would not authorize it to be filled.

From the moment we were introduced to our

court-appointed lawyers, George and I fought to have them recognize

that we were as knowledgeable of the Constitution and the law as

they. We soon realized that we were more knowledgeable then they;

all they knew was what they were spoon-fed at law school.

They knew

nothing about the common-law rights of self-defense, of the

significance of the 14th Amendment citizenship, of the right to

resist unlawful arrest. They refused to combine our cases, kept

trying to put me against George so I would get a lighter sentence,

kept repeating the phrase "We're doing this for appeal." We soon

realized that they were not considering our innocence, but only the

degree of our "guilt."

They didn't expect acquittal, weren't working

for it at all, and only wanted to work toward saving us from the

electric chair.

George and I refused to submit to their plans -

George' s lead attorney tried to quit; mine left town and was

replaced. George' s attorneys did not prepare for trial. They had

not sent the witness subpoenas out in time, so few came.

They had

not examined the forensic reports or questioned potential witnesses

about the officer's violent nature. At trial, the prosecutor

purposely twisted the facts in his closing statement to make it

appear that it was George's bullet - not mine - that killed the

officer. When George and I insisted that I testify to show that it

wasn't George's bullet, George's attorney made the loudest protest.

My attorney begged me not to testify. "George is already lost. Don't

throw away your chance for life. Don't be a hero." I looked him

straight in the eye. "I'm not doing this to be a hero. I'm doing it

because it's the right thing to do."

I had prayed that I would be calm while I was on

the stand, and I was. This, however, was interpreted by the media

and the jury as "cold-blooded lack of remorse." During his trial,

George was pale and tired, and extremely thin. And he knew he was

lost. It was inevitable that he would be convicted and sentenced to

death.

When the jury recommended death for George, the

jailers expected me to cry and wail. Because I showed no reaction

and went about my normal routine, keeping my grief to myself, some

of the jailers turned against me, convinced I was cold and heartless

about George's plight.

It was only after George had been taken away

to prison three weeks later that I broke down. Clutching his last

letter, written hurriedly just before they took him away, I cried

quietly for hours. Half of me had been torn away and now I couldn't

even hope for a glimpse of him in court, and receive his daily

letters of love and encouragement. The reality of our situation only

hit me then, when they took George away to Death Row.

I now had to concentrate on my own trial, which

was getting nowhere. My lawyers and I argued at every meeting

because they refused to even consider the Constitutional issues I

knew were crucial to my case.

One night I perpended the realization

that unless these issues were raised at trial, I could not raise

them in appeal - according to the ABA Rules of Court - and I would

have no basis for a demand of my release. I had no choice but to

fire these useless attorneys and conduct my own trial.

The next morning, at a closed-chamber session

between the judge, my lawyers and me, I presented the lawyers their

dismissals, and copies to the judge. Judge Harper only raised his

eyebrows in surprise and ordered that the lawyers and I discuss this

privately. When we were alone, the lead attorney exploded in anger.

"You arrogant fool. Why do you insist on throwing your life away! Do

you have a death wish?"

I was calm and even smiled a little. "You

are not interested in proving me innocent - only of getting me a

lighter sentence. I want acquittal or nothing. I may lose anyway,

but at least it will be done my way." He stormed out angrily, and

the other attorney shook his head in sympathy. "I know why you're

doing this, but you're making a big mistake. You're risking your

life." I nodded. "I know, but it is my life, isn't it?"

To prepare for trial in the 3 months I had, I

read the Rules of Procedure and Rules of Evidence. I filed several

pre-trial documents, unusual documents that I convinced the judge

were to be introduced as evidence at trial. Fortunately, the judge

was too ignorant of the documents and of Constitutional law to

realize what I filed.

Though he and the prosecutors scoffed at my

pretrial documents challenging his jurisdiction, the

Constitutionality of the statute I was charged under, and the

validity of the indictment based on the original 13th Amendment; I

knew that if I did lose, I still could raise this issue on appeal

because it had been raised at trial.

The trial was a play, scripted by the judge, the

prosecutor, and the restrictive ABA Rules of Procedure. In both our

cases, Judge Harper refused to release the officer' s personnel

record, which showed a long pattern of abuse to the public, and I

was working against a one-sided portrayal of the officer as a "good

cop gunned down in cold blood."

I was able to perform all the

functions of trial in a calm, business-like manner, and even the

judge grudgingly admitted how well I was conducting my defense. But

under the restrictive rules of procedure in today's courts I had

little chance, and I knew it. All I could hope to do was maneuver

the trial to get as much information in my favor on record - for

appeal.

When the jury came back with the guilty verdict I

was not surprised, but it hit me hard. No one can possibly imagine

being alone in a courtroom, feeling the eyes of everyone else upon

you waiting for your reaction to the news that they were going to

put you to death in a most horrible manner.

I forced myself to sit

perfectly still, emotionless, while realizing that the people of

Alabama wanted to kill me for choosing to defend my husband's life.

When it came time for the sentencing portion of

the trial, when I was supposed to convince the jury they should give

me life without parole instead of the death penalty, I waived my

time, telling everyone in that courtroom that I had presented

everything I had at trial. I was not going to beg for my life. When

I was awaiting their decision, I prayed that they would give me

death. If George and I were both on Death Row, we could join our

appeal and fight together.

When the jury recommended death, I rose

from the defense table with as much dignity as I could evoke and

walked through the silent courtroom and hallways back to my cell.

Some of the jailers were upset. One of the women in my cell broke

down and cried.

Execution by electric chair is gruesome. They

shave your head so they can attach the electrodes to bare skin. They

shove cotton up your rectum and put an adult diaper on you because

the charge of electricity through your body causes your bladder and

intestines to evacuate. They put a hood over your face because the

jolt of 20,000 volts causes your face to contort and your eyeballs

to explode.

George and had agreed at the roadblock that we

would fight to the end, and if we still lose and are executed, we

will go back to our Creator knowing that we fought to the end, and

fought for the principle that it is better to have fought and lost

than to submit to those who would rob us of our unalienable right to

liberty.

Heart to Heart

Below are portions of the daily letters George

and Lynda wrote while in the Lee County Jail, Alabama

"When you wrote that you did not blame me for the

plight we're in, it did make me feel much better too. I had been put

in such a difficult spot, and when he reached for his gun, my

reaction was an instinctive one. At that point was one choice: life

or death, to protect myself and my family, or fail miserably.

You

came to my defense, as I would yours, without question. I don't know

of any woman I've ever met who would do as you did for me, and I do

so thank God that we met. " - George

"I'm going through a terrible time dealing with

my captivity here. Yet, there is that hope, that chance for freedom,

and I am clinging to that with the fierceness of a person who is

clinging to the last standing tree in a raging storm." - Lynda

"I have been penalized all my life, as you have,

for adhering to principle, and being honest. I defended my

principles to my own detriment. Everywhere I went, someone wanted me

to yield to a situation, an ideal, or purpose that was wrong - or at

least, wrong for me - and I rebelled. This has cost me dearly

throughout my life. Realizing this, I still am unwilling to forfeit

that what I hold dearest -my integrity." - George

"Though in a moment of total despair I may have

been tempted to entertain thoughts of ending it all here, I've since

come to terms with the fact. that, just as our lives are playing

possibly to the end, so are the lives of those who lied to us and

about us, who prosecuted us, who cheated us and stole from us, who

have unjustly punished us.

Even in this place, captive as I am, I

will not yield my principles. No matter how much I am mocked or

tormented, I will not forfeit my dignity. I will leave this world as

Lynda Lyon Sibley, and with all the pride that entails. I am content

to play this to the end, whatever it might be" - Lynda

I agree with you completely on the result we want

here. Patrick Henry's 'Give me liberty or give me death!' sums up

the way I feel, and all who share the same spirit as you and I, that

mere existence is not life. " - George

'I told her (attorney) I was tired of living my

life to suit others, including an enslaving government, and that

yes, I could have taken the (Florida) sentence and tried to live

under community control, but why? Why should I submit to yet another

injustice? When does a person stand up for the principle of

defending oneself against injustice, rather than submit for the sake

of expediency? Always, I said. I'd rather die than live as a slave

to government control or public opinion. " - Lynda

"I will never give up the fight for freedom,

never! No matter what, I will endure, and I know that you have the

will, determination, and faith to do it too. As you have said before,

they cannot chain our spirits!" - George

"Life in prison is not "life." It is living hell

for someone like you or me. Living in a caged existence where you

are told what to eat, what to wear, where to sleep, when to sit or

stand; where your meager belongings are regularly searched, where

even your body is inspected, where the only intellectual stimulation

you receive is what they allow - what kind of life is that? If the

jury has to choose between death or life in prison, they would be

far more charitable to give us death." - Lynda

"This is one man who won't make a "deal" and sell

his soul for limited freedom." - George

"You carried yourself proudly in the courtroom,

and this is what the jury hated. They wanted submissive, emotional

groveling. They wanted pained expressions of remorse. You are truly

a brave man, Sweetheart, and I am honored to be your wife. " - Lynda

"You have changed me forever, Lynda, and for the

better. I am a whole and complete man with you, and I know that even

if we can't communicate for a while, that you will never forsake me

and will always love me. I know you won't want anyone else, and I

want only you. I will always be faithful to you, my soulmate, and I

will not lose faith in our freedom coming Soon, or in Heavenly

Father's plan for us. " - George

"I tried to picture you in my mind, and the

picture of you I love best is how you look in jeans, your

snug-fitting shirt, and your leather jacket. With your tall, slim

stature and your wavy hair, you looked so incredibly elegant and

handsome. I love your boyish smile and your direct, intense gaze.

Such honesty in that gaze. I love and adore you. " - Lynda

"After all this time apart, sweet Lynda, I will

cherish every moment we have together, every tender caress, every

kiss, every chance I have to see you. My favorite memories are those

of holding you in my arms, sharing a tender kiss or with your head

on my chest. I await the soft warmth of your embrace as I bring you

to the exquisite heights of our lovemaking.

I pledge my eternal love,

and a promise of total and complete loyalty to you. You are one of

Heavenly Father's special daughters, and He has given me the Sacred

duty and honor to love, protect, and guide you, and I will. " -

George

"These months ahead are going to be lonely for us,

George. Please don't let my resignation of our present situation

make you think I will ever let my love grow dim. I think about you

constantly.

Memories make me cry with longing for days gone by. I

want to lay with you once again, caress your body; to snuggle up to

you and your masculine scent, and then feel the warmth of you inside

me as we share love. I am not complete without you. I never will be.

I am yours for eternity. " - Lynda

Block v. State,

744 So.2d 404 (Ala.Crim.App. 1996) (Direct Appeal).

This case involved the death of career police

officer, Roger Lamar Motley, who, during a routine investigation of

a complaint made by a concerned citizen, was killed in the line of

duty.

The prosecution's case against Block was virtually

impenetrable. Block was convicted of the capital offense of murder

under § 13A-5-40(a)(5), Ala.Code 1975. The jury, by a 10-2 vote,

recommended the death penalty; the trial court imposed the death

penalty after a sentencing hearing.

The Defendant, Lynda Lyon [Block], and her common

law husband, George E. Sibley, Jr., lived in Orlando, Florida. In

August 1992, the Defendant and her husband were arrested and charged

with aggravated battery and burglary in a stabbing incident

involving Lyon's 79-year-old former husband.

They entered a plea of nolo contendere to these

charges and a sentencing hearing was set for September 7, 1993. They

failed to appear for sentencing. On September 10, 1993, the

Defendant, Sibley, and her son fled the state of Florida knowing

that a writ of arrest had been issued by the Court.

On October 4, 1993, the Defendant was parked near

Big B Drug[s] in Pepperell Corners Shopping Center in Opelika,

Alabama. She was using a pay telephone outside the store and Sibley

stayed near the car with the child. A passerby, Ramona Robertson,

heard the child ask for help. Worried that the child was in danger,

she kept an eye on the Defendant's vehicle as it moved to a

different location in the parking lot near the entrance to Wal-Mart.

As Sgt. Roger Motley of the Opelika Police

Department came out of a store in the shopping center, Robertson

reported to him what she had observed. Motley, a uniformed officer,

had been running an errand for the police department. After the

situation was reported to him, Motley approached the vehicle of the

Defendant. At that point, Sibley got out of his vehicle as Motley

approached.

Meanwhile, Lyon was using the pay telephone near the

entrance to Wal-Mart. Prior to approaching Sibley, Motley radioed to

the Opelika Police Department as to his activities with respect to

investigation of this incident. A tape recording of those radio

contacts was admitted at trial and played for the benefit of the

jury.

Motley approached Sibley and asked for his

driver's license. Sibley stated that he did not have one because he

had no contacts with the State.

Motley then requested identification

from him. At that point, Sibley pulled a pistol from a concealed

holster on his person and began firing at Motley. Motley attempted

to get away from him and ran behind his vehicle for cover.

The

officer then began returning fire at Sibley. Numerous shots were

fired by Sibley at Motley. The officer was able to fire his weapon

three times at Sibley. Meanwhile, Lyon heard the shooting and ran

toward the patrol car. She pulled a pistol from her purse and began

firing at Motley from his rear or side.

The officer was finally able

to get into his patrol car and radio for help. The patrol car

started to move through the parking lot in an erratic manner,

hitting several vehicles as it moved prior to its coming to a stop

near Big B Drug[s]. Motley was mortally wounded.

The Defendant, Sibley and the child then sped

away from the scene. After a high speed chase, they were stopped at

a roadblock on Wire Road in Auburn, Alabama.

The child was released

and, after a four-hour standoff, the Defendant and Sibley

surrendered to the police. A search of the automobile of the

Defendant uncovered numerous weapons and large quantities of

ammunition.

The police officer had several gunshot wounds.

The fatal shot went through his chest from the front at a slight

downward angle.

The fatal bullet was never recovered and tests were

inconclusive as to which gun fired the fatal shot, although it

appears, from the physical evidence and testimony, that [Block] most

likely fired it. In a statement given to the police following her

arrest, the Defendant admitted firing at the officer three times. At

the time this incident occurred, the parking lot was crowded with

vehicles and people. Numerous witnesses testified at trial as to

being eyewitnesses to the shooting."

The State literally had an airtight case; hence,

the State easily met its burden of proof on each and every element

of the offense of capital murder, in that there was overwhelming

evidence that Block had murdered Opelika Police Officer Roger Lamar

Motley while Office Motley was on duty.

The victim,

police

officer Roger Lamar Motley

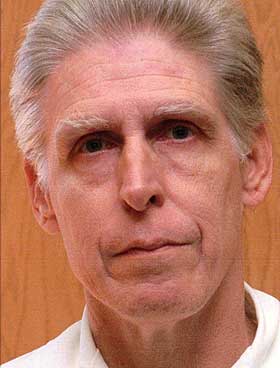

George Sibley Jr., the

common-law husband of

Lynda Block